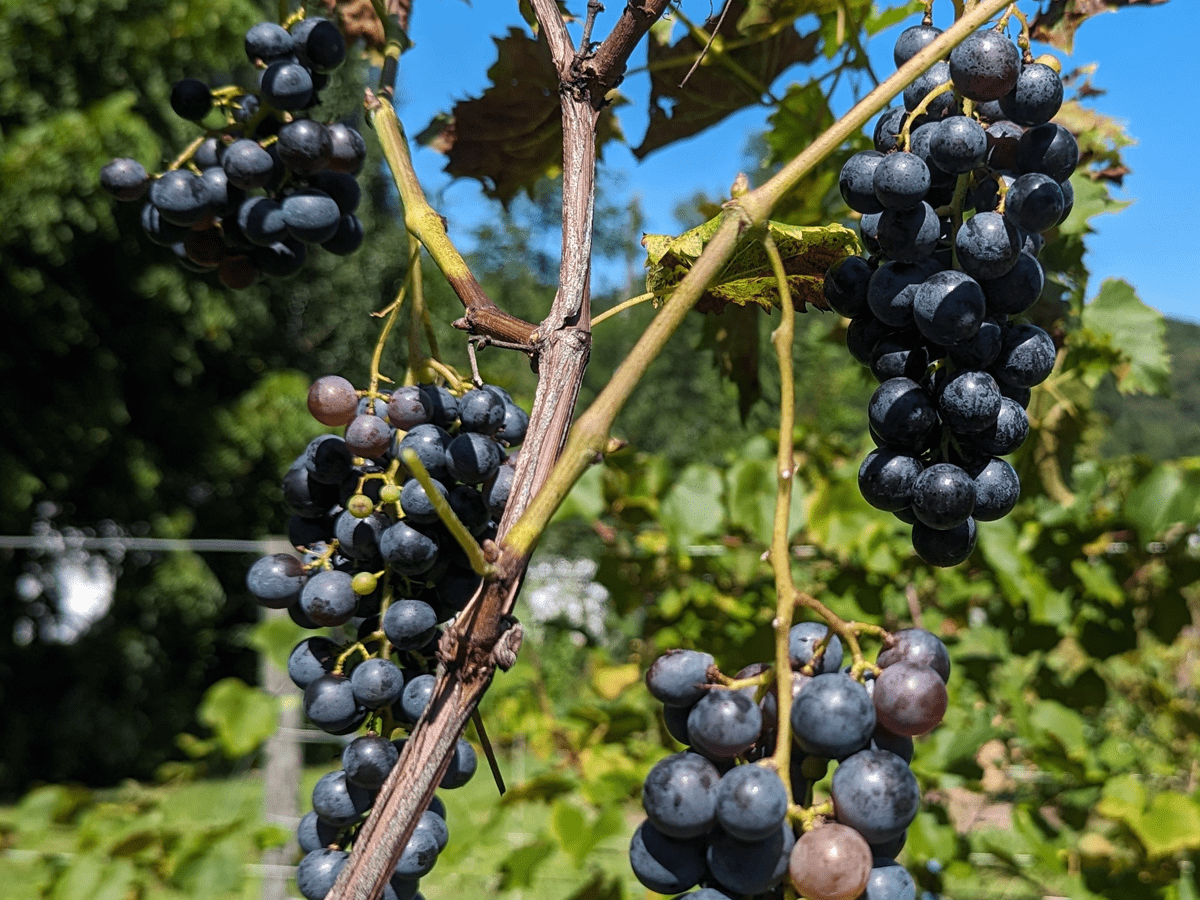

Ruth and I started our vineyard plantings in 2018. Managing our own vineyard, even on a small scale, in this region has taught us a lot about land management and plant health care, as well as the history of grape varieties!

On the Orchard

Five hundred vines went into a half-acre block. Bareroot vines were set out six feet apart in rows eight feet apart. The land sloped to the north, not the greatest for grape growing, but that is what we had to work with. The hilly location is at an elevation of 2100 feet. We’re in Zone 7b where the average winter lows are between 5 to 10∘ F. These winter time temperatures allow us to grow Vitis vinifera including such varieties as Cabernet sauvignon and Chardonnay, the two wines that are virtually household names. However, being the plantsman that I am, I did not limit my plant palette to V. vinifera. I had grown hybrids in Brentwood, NH including Baco noir, Noiret, Landot noir and Marquette, varieties that aren’t exactly familiar to many households! In all, I had selected over 20 varieties to plant including Catawba, Cayuga White, Chambourcin, Chardonel, Cynthiana, Noiret, Traminette, Oberlin noir and Vidal Blanc.

At this point, an explanation of the lesser-known varieties is warranted. Why plant hybrids, and what was the reason for their origination? For their origin, we have to travel to France in 1863, where phylloxera, a nearly microscopic root aphid, was inadvertently introduced. This minute parasite came on stock of vines introduced from the US. Our native Vitis species are resistant to the root aphid including V. labrusca, V. aestivalis and V. riparia (the Fox grape, the Summer grape and the Riverbank grape, respectively). The introduction of phylloxera almost completely devastated the European grape and wine industry! In response, a breeding program began in France to impart resistance to European grapes using American stock. The resulting crossers became known as the French-American hybrids. Examples are Baco noir, Chambourcin, Oberlin noir and Vidal Blanc. However, the wines produced were not the same as pure vinifera, and were judged to be of lower quality. It was later discovered that grafting the European grape onto American rootstock preserved wine quality and European viticulture. The hybrids were summarily ousted from French vineyards.

Vive La Resistance!

But not so fast! The hybrids exhibited hybrid vigor: the vines showed greater winter hardiness and disease resistance (vive la resistance)! They were and are particularly suited to the colder regions here in the States including the Finger Lake region of New York, where Cornell University’s Geneva Experiment Station is located. The French hybrids became the basis of crosses (and back-crosses with V. vinifera) to improve wine quality. Out of the Cornell program came Cayuga White (1972), Chardonel, a cross of Chardonnay and Seyval Blanc (1991), Traminette, a cross using Gewurztraminer and J. Seibel 23-416 (1996), and Noiret (2006).

The Catawba grape discovered in Buncombe County, NC (our neighboring county) is likely a cross of the native V. labrusca and the V. vinifera cultivar Semillon, although its actual origins are unclear. It makes a white or pink sparkling wine, which in 1850 was said to be superior to the Champagnes of France!

Cynthiana (AKA Norton), is a likely cross of the summer grape (V. aestivalis) and V. vinifera. The cultivar dates back to the 19th Century, and has become the state grape of Missouri. It was awarded the best red wine of all nations in Vienna in 1873. We have awarded it the best red wine of Corkscrew Willow Vineyard in 2023!

Interestingly, V. vinifera suffers from diseases that many of the hybrids are resistant to. The major vineyard diseases here are Black rot (Guignardia bidwellii), the most destructive of grape diseases, Downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola), powdery mildew (Uncinula necator) and Phomopsis cane and leaf spot (Phomopsis viticola). All are fungal diseases that develop in wet and humid conditions, of course, those that prevail on the east coast and mid-Atlantic!

Fungicide applications are applied as preventative treatments. They work by inhibiting spore germination or by interfering with fungal metabolism. There are few fungicides that are used in sustainable grape culture, including copper compounds, sulfur, and phosphite. All are applied as foliar sprays.

Choosing the Right Variety

Growing sustainably requires elements of plant selection. Along these lines, we are limiting the vinifera cultivars grown here. One of the concerns here in NC are early spring frosts. Varieties that are early to break bud are at higher risk of losing its crop. This has been our experience with Chardonnay. It is the first to break bud in the vineyard, and hence has been a poor producer. On the other hand, Chardonel (a cross of Chardonnay and Seyval Blanc) breaks bud weeks later, and has been a good producer. Vidal Blanc is the last to break bud, and last to mature fruit, as a consequence is an excellent producer in the vineyard.

Surprisingly, Marquette a hybrid developed by the University of Minnesota, hardy to -30 F, breaks bud early and is susceptible to spring frosts. Though it made a very good wine in NH, it is not well adapted here.

Climate is determining what we can grow in our vineyard. In a way, the smaller selection, the greater the harvest. Of the 20-some-odd cultivars we planted, we have distilled them to a handful. Our featured wines to come are Cynthiana (a red), Vidal Blanc (a white), and Catawba (a sparkling). The other cultivars that are doing well here include Chambourcin and Noiret (reds), Cayuga White, Chardonel and Traminette (whites).

Next time, we’ll talk more of viticulture from the ground up!

~ Signing off for now, Joe