Some plants just take over the world! Most are non-native plants that were either intentionally or inadvertently introduced into cultivation. Many have become invasive and widespread, and without naturally occurring controls, are out competing native flora, resulting in a decrease in species diversity. A veritable tangle of brambles run wild! Though a prickly subject, a discussion of the top ten least wanted follows.

Asian Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), native to eastern Asia, it is a member of the bittersweet (Celastraceae) family. Often seen growing at the woodland edge, left uncontrolled, it compresses the trunk of trees with its twining habit. A constrictor of the vining world. It is dioecious (that is, male and female plants), with the females produce orange-red fruit that are spread by birds. It is difficult to control, but may be managed by cutting the stem low to the ground and dabbing herbicide to the fresh cut. Always follow label directions on the use of approved products.

Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis), native to Europe and Asia, is a member of the morning glory (Convolvulaceae) family. It is an aggressive vining plant, and though its flowers are attractive, it has a tenacious system of rhizomes that make it difficult to eradicate. Grows in open fields, lawns and disturbed areas. We keep it in check by regular mowing.

English ivy (Hedera helix), native to Europe and eastern Russia, it is a member of the ginseng (Araliaceae) family. English ivy is tolerant of partial shade, and can grow into the tree canopy reaching 80 feet! Interestingly, it has a juvenile and adult form. The juvenile plant is vining, with pointed leaves, the adult is shrubby, with rounded leaves. Its flowers are produced on structures “umbels”, producing dark blue fruit, which are toxic. It is aggressive in forest settings, and competes with native wildflowers and regenerating tree saplings. Difficult to control once established, it is best to cut and dab the fresh cut vine with an effective herbicide.

Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) is a native vine in the greenbrier (Smilacaceae) family, growing in hedgerows and thickets. Its’ stems are green, thorny (hence, well named) and it spread by rhizomes. The new shoots are edible, much like asparagus, and perhaps that is a way to control its invasiveness in cultivated plots!

Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) is native to eastern Asia. It is a twining vine with fragrant yellow and white flowers. It is considered invasive, though I have fond memories of sucking the nectar from the flowers as a youngster! It grows in disturbed places, along roadsides, preferring full sun. It will climb into trees, but tends to invade trees along the edge.

Kudzu (Pueraria montana) is native to Asia and Australia, a member of the legume (Leguminosae) family. Found growing along roadside thickets, fields and in trees. It is very aggressive, killing trees by completely covering the canopy. First introduced as forage and for slope stabilization, an introduction that sadly went badly wrong!

Multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora) is native to Asia, a member of the rose (Rosaceae) family. Introduced to control erosion, its brambling, thicket-forming aggressive habit makes one wonder “what were you thinking” to introduce the plant? Stems are green with prickles and the seed is spread widely by birds that feed on the ripened hips.

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) is native to North America, and a member of the cashew (Anacardiaceae) family. It grows along roadsides, thickets, fences and in woodlands. It causes a contact dermatitis, that most find considerably unpleasant. It is readily identified when growing, having three shiny leaves that turn red in fall. The stems cling by means of short, dark aerial roots, which is also diagnostic. All parts of the stem contain the toxic principle urishiol. Control by repeat mowing, alternatively cut stems and apply an approved herbicide. Never burn the vine, as the toxin becomes airborne. The fruit is a white drupe often eaten by birds, which drop the seeds to start new vines.

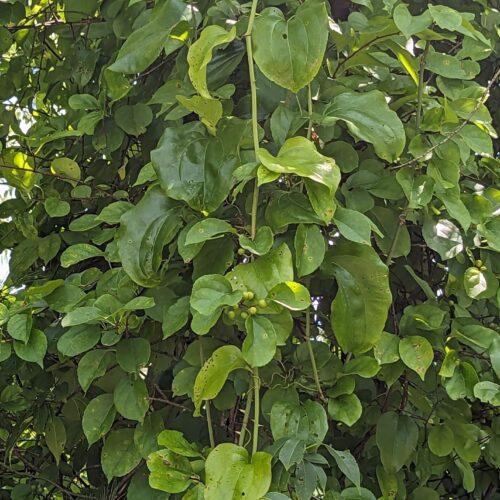

Porcelain berry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata), native to Asia, is a member of the grape (Vitaceae) family. It is an aggressive vining plant that forms berries of varying colors: blue, lavender, pink, purple, which was its attraction to being introduced into cultivation. Birds likewise spread the plant by eating the ripened fruit. It invades forest edges, pond edges and disturbed areas.

Russian Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) is native to Asia and Southern Russia, a member of the oleaster (Elaeagnaceae) family. It has grayish foliage, forms a large shrub and is armed with thorns. The drupe-like fruit (achenes) are eaten by birds that happily spread the plant. It produces fragrant flowers in spring and prefers sun and moist soils.

Bonus Plant

Northern dewberry (Rubus flagellaris) is a native plant of the rose (Rosaceae) family that behaves like a ground-hugging vine. It produces trailing stems up to 15 feet and roots at the nodes, which is its primary means of spreading. It has hooked prickles and produces fruit on second year wood. It has the annoying habit of sending one tripping. Unfortunately, foul language has so far had no effect on controlling its growth!

SIDEBAR: The difference between prickles, spines and thorns

Prickles arise from the epidermal cells. They are corky, sometimes hooked projections modified to prick, but easily broken off, usually into your fingers! Roses and blackberries have prickles.

Spines arise from a stipule or modified leaf. Quince is armed with spines.

Thorns are modified stem tissues that come to a sharp point. Callery pear, hawthorn and greenbrier have thorns.

In writing about such differences, it is my intent is to make these three points (prickles, spines, thorns) clear!

Join me next week when we discuss soil health.

~ Signing off for now, Joe