This is the first part of a two-part series of the shade trees of summer. In this post we’ll discuss honey locust, American sycamore, willow oak, tuliptree, and Weeping Purple European beech.

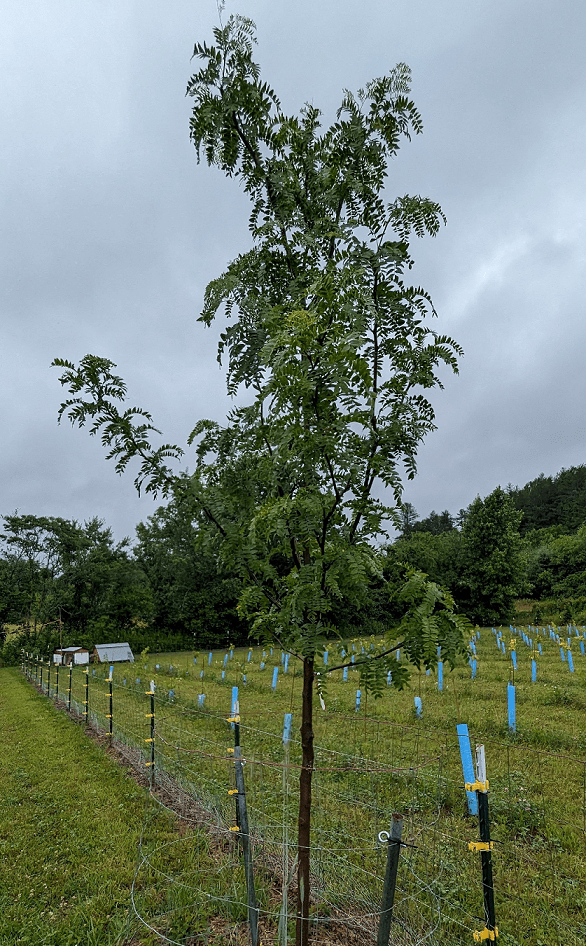

Honey locust is a member of the legume (Fabaceae) family, and as such forms root associations with rhizobial bacteria, which fix atmospheric nitrogen. In exchange for bacterial nitrogen, the tree provides sugars to the resident bacteria. As its name implies, the species has thorns which are branching (tri = three, acantha = thorn); but the cultivar, ‘inermis’ is thornless (literally, a three-thorned thornless tree)! A native tree, it is attractive to pollinators making it a great wildlife habitat tree. Trees have fine, pinnately divided foliage. There are several cultivars in the nursery trade. Here, we’ll discuss two. Plant them in full sun, top dress with compost or other organic matter, and mulch well.

Some potential problems include borers, spider mites, webworms, gall midge and powdery mildew. Managing pest issues starts with keeping trees healthy including, watering, fertilization and avoiding bark injuries by keeping mowers and string trimmers away from the base of the tree.

‘Shademaster’ is upright and vase-shaped. It has been planted (perhaps, overplanted) in street tree plantings to replace the American elm. It has dark green foliage, is fast growing and casts dappled shade, allowing turf and ground covers to be planted under its canopy. Fall color is yellow. It does not set fruit, so fall clean-up is easy.

‘Sunburst’ honey locust has yellow foliage in spring, becoming green in summer. It is also thornless and podless. It provides early interest in the spring months. Plant as a specimen tree.

American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) is a native tree that makes its home in wet (riparian) bottom lands. It is also called American planetree (alluding to growing in the planes), and buttonwood (alluding to the fruit, which occurs as a buttonball). Ecologically, it is a pioneer species, but is long-lived (200+ years) if allowed to grow. The tree is cultivated for its exfoliating bark which is mottled greenish-gray, white and brown. Early settlers even camped inside hollow sycamore trees that were 12’ across! The large dark green leaves are reminiscent of the maple leaf in shape, and presents a coarse texture in the landscape.

American Sycamore is susceptible to anthracnose (Apiognomonia veneta), which in cool wet springs causes the tree to defoliate. Sycamore anthracnose is a fungal infection that attacks leaf veins and twigs, causing defoliation and dieback. In older trees with repeated infections, the branching becomes zig-zagged.

A chance hybrid found in Europe in the 17th century between Platanus orientalis (oriental plane) and the American Sycamore gave rise to the London planetree (Platanus x acerifolia). The hybrid tree shows improved resistance to anthracnose and is more tolerant of city conditions. Plantings in urban environments have largely replaced the native tree with the hybrid.

Pollen from the American Sycamore can cause mild to severe reactions in people allergic to it (including me)!

Although some take issue with early spring defoliation (i.e., why am I raking leaves in the spring?), the buttonballs and allergens, it is a tree worth considering for species diversity, if no other reason. Defoliation in spring only occurs in cool, wet springs. The tree will re-foliate in late spring. It has an interesting mottling, in my opinion, superior to the London plane, and after flowering, is a great shade tree of summer.

The tree has a diffuse vascular system that is active for 20+ years, which imparts a measure of resiliency. One of the most effective approaches to maintaining tree health, particularly following a defoliation event, is to keep the tree adequately watered and mulched, particularly in dry conditions. To improve soil condition, make annual applications of humic acids, liquid seaweed, and molasses. These will create a soil environment favorable to roots and endo-mycorrhizae on which the tree depends. Examples of formulations that add to soil conditioning are EnviroPlex (22% organic acids), SeaXtra (an extract of Ascophyllum nodosum), and Bio MP (5-3-2 plus molasses).

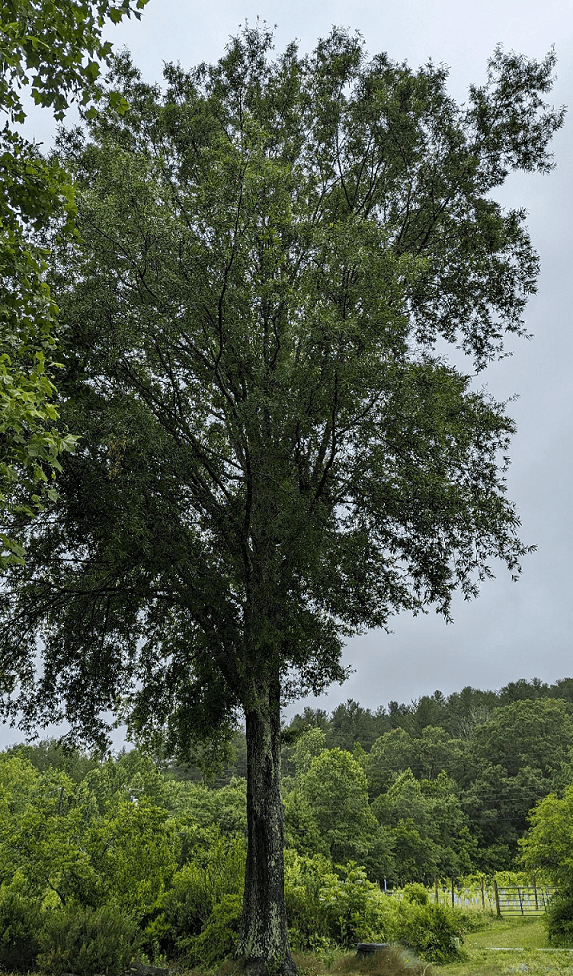

Willow oak (Quercus phellos) is a member of the oak and beech family (Fagaceae). Although grouped with the red oaks, its leaves are narrow and strap shaped somewhat reminiscent of willow. In appearance, the canopy presents a fine texture. And like willows and sycamores, it tolerates moist, clayey soils. It is native to the southeastern United States, but is hardy to USDA zone 5. It forms an oval crown growing up to 100 feet, but more typically 50 to 75 feet.

Though oaks are host to defoliating insects (e.g., spongy moth) and root rots and canker diseases, willow oak has good pest resistance and is a long-lived tree that tolerates city conditions. Acorns are a source of food for wildlife.

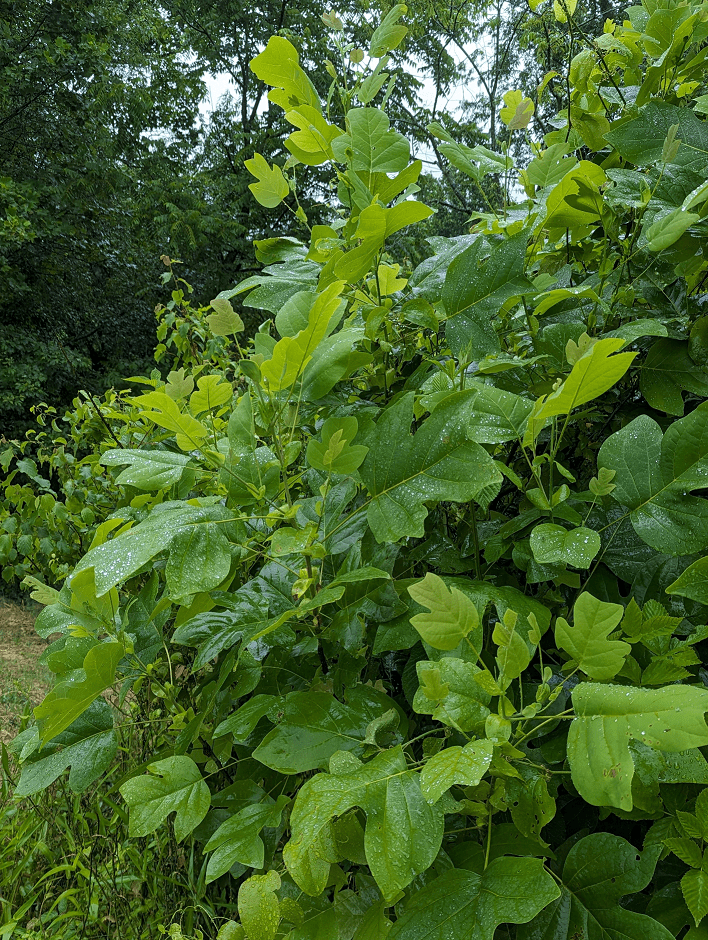

Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera) is a member of the Magnoliaceae. The specific epithet means “tree that bears tulip shaped flowers.” It is native to the eastern US and prefers to grow in moist, rich, well drained soils. It forms a broad conical to pyramidal canopy. It is grown as a shade tree and presents a coarse texture in the landscape. The silhouette of the leaf is in the shape of a tulip flower. It can grow to 100 feet tall, often identified as the straightest tree in the woods.

On occasion, it will get infested with aphids and soft scales. These pests produce a sticky honeydew that could be problematic around built structures, such as a patio. In the event that control is required, a systemic treatment of imidacloprid such as IMA-jet, will manage infestations effectively.

Weeping Purple European Beech (Fagus sylvatica pendula purpurea) is a member of the oak (Fagaceae) family. Its specific epithet means “forest-loving.” The species has an upright growth habit and dark green leaves, and smooth, dark gray bark. It is native to central and southern Europe, with a broad, oval crown that is wider than tall. It is a very slow growing ornamental tree.

Most recently, a nematode (Litylenchus crenatae) introduced into the eastern US and Canada is causing a decline in beech. Beech leaf disease presents as leaf striations and was first identified in the Holden Arboretum in Ohio. It is now found in Maine, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut New York, Long Island, and northern Virginia. It infects both native and European beech trees.

The weeping purple leaved beech prefers rich, loamy well drained soil. Plant in full sun to part shade. Mulch trees well. It is slow growing, but forms a unique specimen in the landscape.

An interesting cultivar is the Purple Fountain Beech (F. sylvatica ‘Purple Fountain’), a sport of the weeping purple European beech. It is narrower in habit compared to the F. sylvatica pendula purpurea. Also a slow-growing tree, it will grow to 25’ and only 15’ wide. Purple leaves and narrow columnar in shape, with cascading leaves, it is more suitable to the small property. Plant as a specimen tree in full sun to partial shade.

In the next series of the Shade Trees of Summer, we’ll consider five additional trees worthy of consideration including Black walnut, Red and Sugar maples, Chestnut and American elm.

~ Signing off for now, Joe